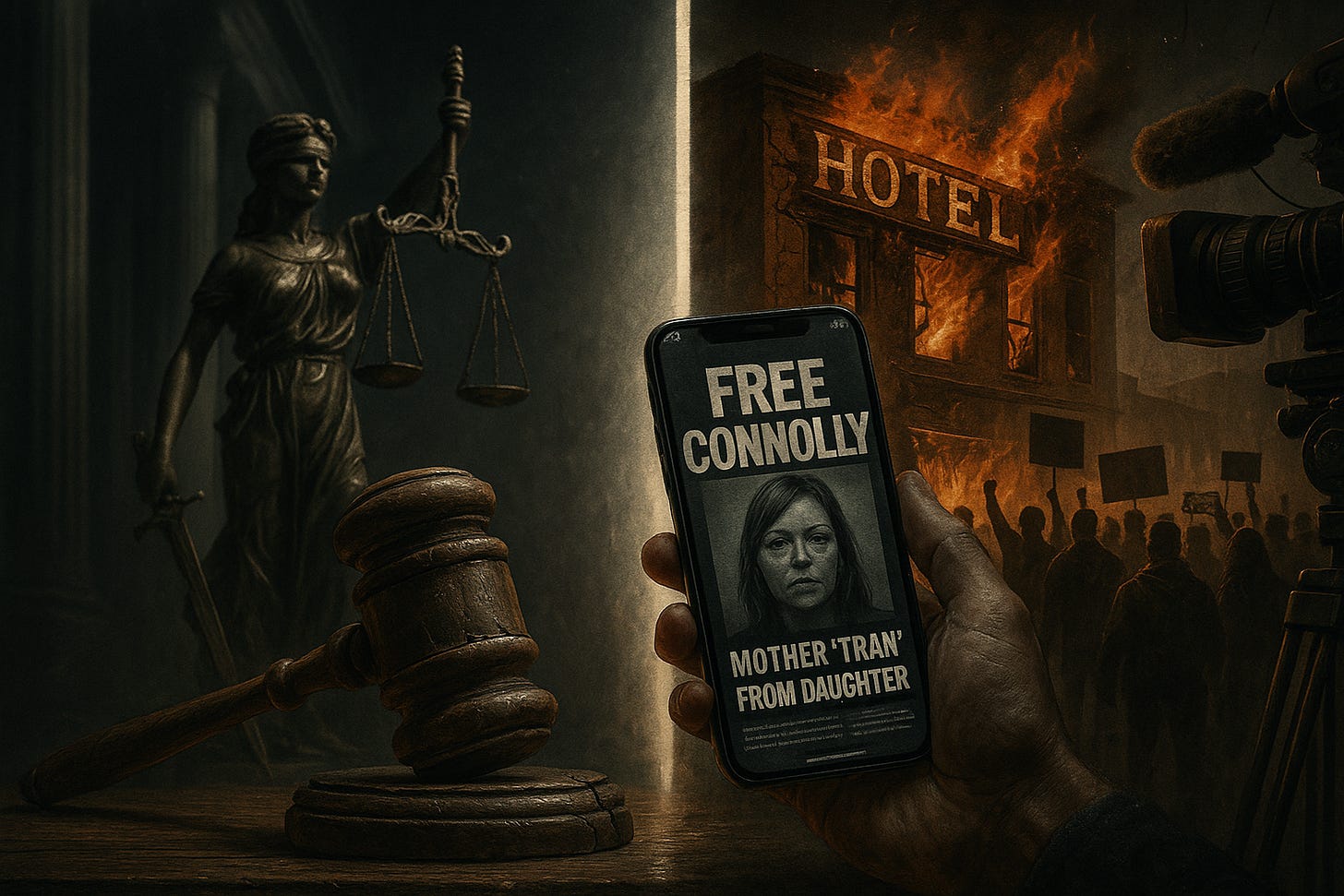

Lucy Connolly’s case exposes the fault lines in Britain’s justice system where codified law, natural fairness, and media framing collide. She pleaded guilty, her appeal failed, yet her supporters recast her as a martyr. This is not new; it is part of a long arc in Britain’s uneasy relationship with free speech.

Connolly’s case has become a prism for Britain’s contradictions on free speech and justice, but she is no innocent. A calculating and unapologetic racist, she tweeted in the aftermath of the Southport killings, calling for the burning of hotels housing asylum seekers. This was not a slip of the tongue or a rash, grieving outburst. She admitted in police interviews that she “did not like illegal immigrants” and had sent similar messages both before and after the tragedy. A WhatsApp she sent privately the day before her arrest, “the raging tweet about burning down hotels has bit me on the arse lol”, shows full awareness of what she had done. She leveraged her own incarceration as a badge, presenting herself as a victim rather than as the instigator of vile speech.

She was convicted under Section 19 of the Public Order Act 1986, a statute originally designed to deal with the National Front but now extended into the digital era. The CPS emphasised that she was jailed not for merely “hurtful words” but for inciting racial hatred, with a 31-month sentence reflecting proven intent and the mass reach of her message. Her guilty plea only moderated the term. Article 10 of the ECHR, absorbed into British law by the Human Rights Act 1998, guarantees freedom of expression but allows restrictions for public order and protection of others. Connolly’s case shows those restrictions being enforced, not bent.

Statistically, the disjuncture is plain. The Sentencing Council guidelines for stirring up racial hatred allow for up to seven years’ custody. Connolly received less than half of the maximum. Yet violent offenders often receive less. According to Ministry of Justice data (2023), the median custodial sentence for actual bodily harm was 18 months, with nearly a third suspended. Offenders convicted of sexual assault on an adult often receive less than three years. When Connolly’s words drew 31 months, the public instinctively saw an imbalance: words were punished more harshly than violence. Calls of two-tier justice have grown louder in the past year, often fuelled by right-wing agitators eager to discredit Labour since it came to power. For the record, many criticisms can rightly be levied at Labour and other parties, whether in power or not, but that is a different story.

Comparisons sharpen the point. From the English Defence League rioters in 2011, many of whom avoided long custodial terms, to a Manchester attacker whose violence earned only a suspended sentence, to a performer like Bob Vylan shielded under artistic freedom, and Labour councillor Ricky Jones acquitted despite being filmed urging a crowd to “cut their throats” Connolly’s harsher sentence exposes the uneven application of law between speech and violence. Here lies the fault line: a middle‑aged woman condemned for a single racist post is locked away, while others who incite violence under different guises avoid serious sanction. To the public, such distinctions look like double standards. The law’s impartiality in theory becomes, in practice, a hierarchy of speech where context shields some and damns others a selectivity that corrodes faith in justice.

The paradox here is that impartial codified justice collides with natural justice. Codified justice is the formal application of statute and precedent rules written into law, applied consistently regardless of circumstance. Natural justice, by contrast, is rooted in instinctive fairness: the idea that like cases should be treated alike and that punishment should feel proportionate to the offence in both scale and moral weight. In Connolly’s case, codified justice treated her tweet as a grave offence because of its intent and reach. Yet natural justice recoils at words being punished more harshly than violence. The more rigidly the courts defend their independence through strict adherence to codified frameworks, the more legitimacy ebbs away when outcomes appear detached from society’s basic sense of fairness.

This perceived hierarchy of speech, where some are shielded and others condemned, feeds directly into broader mistrust of the justice system. What has accelerated Connolly’s afterlife is the media’s role in creating what can only be described as a martyr syndrome. Right‑wing figures like Richard Tice and Laurence Fox raised tens of thousands in her name, painting her as a prisoner of conscience rather than a racist arson‑monger. Headlines reframed her as a mother “torn from her child” rather than a woman who called for mass violence. Left‑wing outlets, meanwhile, retorted that the case showed the need to be firmer on hate speech, but their focus on comparative leniency elsewhere only reinforced her elevation into symbol. In other words, the gap between codified justice and natural justice is amplified by media framing, turning Connolly from an offender into a lightning rod. The more indefensible her actions, the more she became defended in partisan media frames.

The phenomenon is not new. Britain has always punished speech disproportionately when it threatened authority. In the 18th century, radical publishers like John Wilkes were hauled before the courts for seditious libel after criticising the Crown. In the 19th century, campaigners such as Richard Carlile spent years in prison for distributing Tom Paine’s Age of Reason, considered blasphemous at the time. Even into the 20th century, cases like Whitehouse v. Gay News (1977) saw editors convicted of blasphemy for publishing a poem. The censorship of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover under the Obscene Publications Acts carried the same logic: silence the voice, protect authority, preserve order. Today, a woman who gloried in incitement becomes a lightning rod in that same tradition. She manipulates her punishment into a platform, while her supporters translate the law’s impartiality into political bias. The continuity is striking: from Wilkes to Carlile to Connolly, the British state has repeatedly chosen to over‑penalise speech when it perceives a threat, making her case less an aberration than part of a long historical arc.

The numbers show the system’s tension, but they also dismantle the myth of Connolly as an unfortunate casualty. Home Office statistics record over 8,000 racially aggravated offences leading to charges each year, yet only a small fraction progress under stirring‑up hatred provisions. Those provisions are reserved for the most calculated and egregious cases. Connolly’s inclusion was not accidental, nor trivial: it was the product of deliberate intent, the scale of dissemination, and her persistence in expressing racist hostility. Far from being an ordinary mother unfairly swept up, she was singled out because her conduct crossed the high threshold of criminal incitement. That selectivity makes her case appear unique to outsiders, but uniqueness does not equal persecution. It highlights why she has been able to posture as a victim, exploiting the perception gap to claim martyrdom. The reality is clear: she was prosecuted because she qualified for the narrow band of offences the law reserves for those who actively seek to inflame hatred.

Lucy Connolly was not crushed by a politicised judiciary; she was convicted for deliberate incitement. Her case instead lays bare the fragility of Britain’s free speech framework, stretching from the residual liberties of the 17th century to the qualified rights of Article 10 today. Judicial independence may shield the courts from political interference, but it cannot shield them from public disquiet when sentences for speech eclipse those for assaults or riots. Into that gap steps a media eager to canonise the guilty, inflating Connolly into a martyr. She deleted her tweet, but not the intent behind it. What endures is not contrition, but the spectacle of justice distorted by those determined to defend the indefensible, ensuring that her notoriety outlives her punishment.

Free speech in Britain has never been absolute. Before Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights was absorbed into domestic law in 1998, expression was treated as a residual liberty tolerated until specifically restricted. The Bill of Rights 1689 only protected MPs within Parliament. The Licensing Act 1662 imposed prior restraint on printers until it lapsed in 1695. Common law offences of sedition and blasphemy curtailed political and religious dissent. The Public Order Act 1936 targeted fascist rallies, while the Obscene Publications Act 1857 censored literature. In that historical context, Connolly’s conduct would not have been outside the reach of the law: speech deliberately urging violence could have been prosecuted as seditious libel, incitement to arson, or disorder. Crucially, she pleaded guilty in court, acknowledging the offence, and her subsequent appeal failed, reinforcing that due process was followed and that the conviction was upheld on review. Attempts to frame her prosecution as legal malpractice or political persecution serve mainly to muddy the waters. Article 10 provides a modern balancing clause, but even without it, her conviction under long‑standing British legal traditions would have been assured.

Statistical trends show how the landscape has evolved. Before the Human Rights Act 1998, prosecutions for speech were most often framed as blasphemy or obscenity, with more than 60 such trials between 1970 and 1990. After Article 10 was domesticated, those older charges faded, replaced by prosecutions under the Communications Act and Public Order Act. In 2015, nearly 2,000 people were convicted of communications offences; by 2023, that figure had fallen to just over 1,100, even though police were making around 12,000 arrests, roughly 30 every day, for offensive online speech. The attrition between arrest and conviction highlights how the law filters trivial cases from serious ones. CPS data further confirms that prosecutions for stirring up hatred are rare and reserved for the most severe examples. Seen in this light, Connolly’s conviction is not an aberration but part of a long statistical arc: evidence that the state consistently prioritises curbing deliberate incitement when speech is likely to ignite disorder, regardless of whether Article 10 exists or not.